Interested in learning about Lawrence Kohlberg? You’re in the right place! Kohlberg’s work has had a major impact in the fields of education and criminal justice.

Who is Lawrence Kohlberg?Lawrence Kohlberg’s Childhood and FamilyEarly EducationActivismEducational BackgroundHow Did Kohlberg Develop His Theory of Moral Development?How to Apply Kohlberg’s TheoryLawrence Kohlberg’s Books, Awards, and AccomplishmentsWas Lawrence Kohlberg Married?Lawrence Kohlberg Death

Who is Lawrence Kohlberg?

Lawrence Kohlberg’s Childhood and Family

Early Education

Activism

Educational Background

How Did Kohlberg Develop His Theory of Moral Development?

How to Apply Kohlberg’s Theory

Lawrence Kohlberg’s Books, Awards, and Accomplishments

Was Lawrence Kohlberg Married?

Lawrence Kohlberg Death

Laurence Kohlberg was born on October 25, 1927 in Bronxville, New York. His parents were Alfred Kohlberg and Charlotte Albrecht Kohlberg. Kohlberg was the youngest of his parents’ four children. His older siblings were Marjorie, Roberta, and Alfred.

Kohlberg was raised in a very wealthy family. His father was a Jewish German entrepreneur who operated an import business and his mother was a Christian German chemist. Although their money afforded them privileges, Kohlberg’s family was not very stable. The main reason for this was his parents’ troubled marriage.

Kohlberg was an excellent student. When he graduated from junior high school, his yearbook prophesied that he would grow up to be a “great scientist and Nobel Prize winner.” Kohlberg’s father hired a tutor to teach him Latin and Greek to prepare him for enrollment at Phillips Academy Andover. His schoolmates there described him as a rebel, a lover of adventure, and an intellectual who enjoyed reading Plato.

During his time at Phillips Academy, Kohlberg began to focus more on his Jewish-German heritage. He closely followed the events of World War II, particularly how the Nazis treated the Jews in Europe. After he graduated from high school, an eighteen years old Kohlberg signed up for the United States Merchant Marines. He spent the next two years on board theUSS George Washingtontraveling Europe, observing the aftereffects of World War II and meeting people who survived the Holocaust.

Kohlberg was released from the detainment camp three months later after members of the Haganah submitted papers with false names to the British forces. He travelled to Palestine to support the Jews during the 1948 Palestine war against the Arabs, but refused to participate in the actual fighting. He lived in an Israelikibbutz(a collective community that is traditionally based on agriculture) before returning to the United States in 1948.

Kohlberg’s wartime experiences cemented his Jewish identity and strengthened his resolve to pursue “social justice for all.” He changed his first name from “Laurence” to “Lawrence” perhaps to indicate his identity achievement. Although he played a part in helping many of the Holocaust survivors, questions of morality soon came to the fore. He strongly questioned whether helping the Jewish refugees justified the extreme means he and members of the Haganah had taken during the war.

Kohlberg entered the University of Chicago in 1948, soon after his return to America. As he received high marks on his examinations, he was excused from several required courses and was able to earn his bachelor’s degree in psychology in less than a year. After completing his first degree, he was unsure whether to become a clinical psychologist or a lawyer in order to continue his fight to advance social justice. He spent much of his time reading the works of various philosophers and psychologists such as Plato, Socrates, John Locke, Immanuel Kant, John Stuart Mill, and John Dewey.

In 1958, Kohlberg moved to New Haven, Connecticut to join Yale University as an assistant professor of psychology. He moved to Palo Alto, California in 1961 when he became a fellow at the Center for Advanced Study in Behavioral Sciences. In 1962, Kohlberg accepted an offer from the University of Chicago to join their faculty as an assistant professor before he was promoted to associate professor of psychology and human development.

Kohlberg joined the faculty at the Harvard Graduate School of Education in 1968 and was appointed Professor of Education and Social Psychology. He founded the Center for Moral Education and Development in 1974, which soon attracted scholars from around the world and became a whirlwind of research, training, and educational activities. Kohlberg remained at Harvard for the rest of his professional life.

After reading the story, the boys were asked if Heinz should have stolen the drug. Kohlberg was particularly interested in the rationale for their answer so he followed up with a series of probing questions, such as: Does Heinz have an obligation to steal the drug? Is it important for people to do everything they can to save another life? Is it against the law to steal? Does that make it morally wrong?

Kohlberg’s Theory of Moral Development

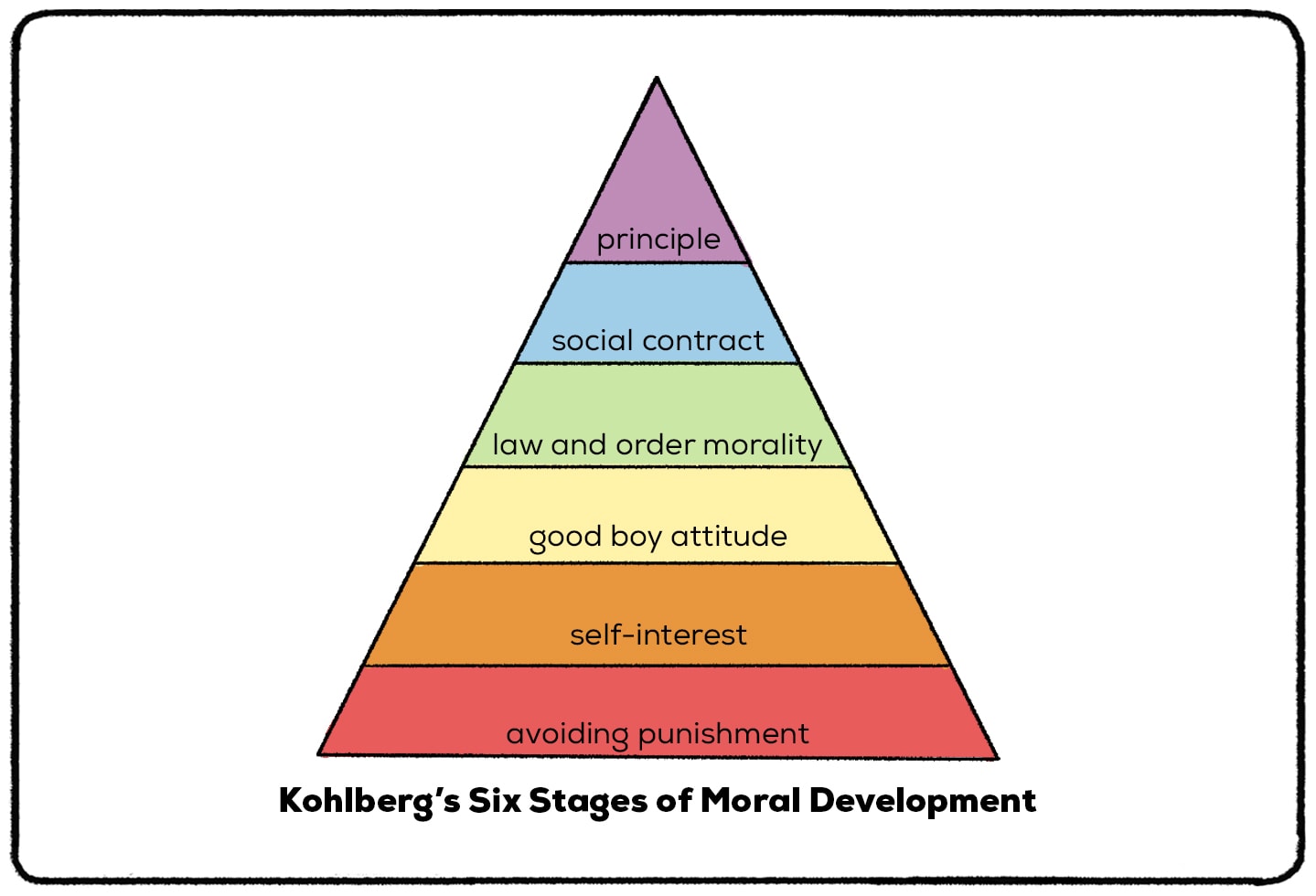

After analyzing participants’ responses to a series of such dilemmas, Kohlberg concluded that moral development, or moral reasoning, progresses gradually through three levels, each consisting of two stages. According to Kohlberg, there is no variation in the order of the stages. Each successive stage develops from, and replaces the one, immediately preceding it.

How did Kohlberg Measure Moral Reasoning?

Although he suggests that moral reasoning becomes more sophisticated with age, Kohlberg did not attach fixed age ranges to his developmental stages. People move through the stages at different rates and many never reach the highest stage. The first two stages are typical of young children and delinquents, while stages three and four are characteristic of older children and adults.

The levels and stages are as follows:

Level 1: Preconventional Morality

At this level, morality is externally controlled and decisions are made based on the rules of authority figures. Actions are judged based on their consequences—those that lead to rewards are viewed as good; those that result in punishment are considered bad.

Stage 1: Punishment and Obedience Orientation- Children at this stage have a hard time considering more than one perspective in a moral dilemma. Moral decisions are based on obedience to authority and fear of punishment. People’s motives and intentions for acting tend to be ignored. (Example: “You shouldn’t steal the drug because you’ll be caught and sent to jail”).

Stage 2: The Instrumental Purpose Orientation- Children begin to recognize that a dilemma can be viewed in different ways. However, the decisions they make are based on self-interest. Actions are considered good and right if they result in benefits for the self or loved ones. (Example: “By stealing the drug, Heinz is running more risk than it’s worth”).

Level 2: Conventional Morality

Individuals at this stage still consider obedience to social rules and laws important. However, their reasons now move beyond self-interest.Conformity to social rulesis seen as necessary for maintaining good relationships and societal order.

Stage 4: The Social-Order-Maintaining Orientation- Moral decisions are not just based on maintaining close personal relationships, but on maintaining the wider social order. Individuals at this stage believe laws should be applied in the same way for everyone and that each individual has a personal responsibility to obey them. (Example: “Even if Heinz’s wife is dying, it’s still his duty as a citizen to obey the law. No one else is allowed to steal, why should he be?”).

Level 3: Postconventional Morality

This is the highest level of moral reasoning. Ideas about right and wrong are based on broad principles of justice, which may or may not coincide with laws and orders from authority figures. Kohlberg believed very few individuals actually progress to this level of morality.

Stage 5: The Social-Contract Orientation- Laws are viewed as a means of advancing human welfare and as social contracts which people are required to uphold because they bring about more good than if they did not exist. However, laws are deemed worthy of being challenged if they undermine basic human rights and dignity. At this stage, individuals begin to recognize that what is legally right may not necessarily be morally proper. (Example: Although there is a law against stealing, the law wasn’t meant to violate a person’s right to life, so Heinz is justified in stealing in this instance).

Stage 6: The Universal Ethical Principle Orientation- Moral judgments are based on self-chosen principles of ethics and justice. These abstract principles (e.g., respect for the worth and dignity of each individual) are universal in that they apply to all humans regardless of social norms and laws. They also supersede any concrete rules that may conflict with them. (Example: “If Heinz does not do everything he can to save his wife, he is putting respect for property above respect for life itself. People have a mutual duty to save one another from dying”).

In educational settings, Kohlberg’s theory gives teachers an idea of the level of moral decision-making they can expect from students based on their age. Such knowledge can help to guide behavior management strategies. For example, children at the preconventional level tend to focus on the consequences of their actions when making moral decisions. Teachers of such students should therefore establish clear guidelines for appropriate behavior and ensure that students are aware of the consequences of acting outside of the specified rules. This could help to prevent unwanted behaviors such as stealing and bullying.

Group discussion of moral dilemmas has also been included in some correctional treatment programs. The goal of such discussion is to raise the level of moral reasoning among delinquents and criminal offenders. Among this population, a large percentage has been found to operate at Stage 2 of the preconventional level, where self-interest is paramount. The hope is that through discussions of moral conflicts and their resolutions, offenders will gradually grow to the level of conventional moral reasoning where they begin to consider the perspectives and feelings of others. Existing evidence suggests that this type of moral education is indeed effective in improving moral reasoning and that enhanced moral development results in reduced criminal activity.

While Kohlberg’s theory did much to propel the study of moral development, his work has sparked numerous criticisms. Some of these are noted below:

Gender bias

Kohlberg only included male participants in his research on moral development and the main character in most of his dilemmas were male. As such, critics argue that his theory is biased toward males and does not provide an adequate description of morality in females. Carol Gilligan, one of Kohlberg’s foremost critics, noted that he focused primarily on issues of rights, justice and fairness as key components of morality. Other issues, such as care for others, compassion, and attachment, which play a greater role in female moral reasoning, are largely ignored.

Order of stages

According to some scholars, moral reasoning does not progress in as orderly and uniform a manner as Kohlberg’s theory suggests. Individuals may employ more than one level of moral reasoning at a given point in time, or may revert to a lower level of reasoning depending on the situation in which they find themselves. Moral reasoning is therefore not only age-dependent, as Kohlberg proposed, but context-dependent as well.

Predictive value

Another limitation of Kohlberg’s theory is that it often fails to predict moral behavior accurately. In many cases, discrepancies have been found between the way peoplereasonon moral issues and the way theyactwhen facing such issues in everyday life. It has also been found that individuals at different stages of moral development sometimes make similar moral decisions, while those at the same stage of reasoning may act in morally different ways.

Hypothetical dilemmas

One reason offered for the limited predictive value of Kohlberg’s theory is that it was developed on the basis of hypothetical and artificial dilemmas. Many of Kohlberg’s dilemmas, including the Heinz dilemma, would have been unfamiliar to research participants and the moral choices they make in a research setting would have no real consequences for them. People may reason and behave quite differently when facing real-life situations in which they actually have something to lose.

Postconventional morality

Social and emotional influences

Kohlberg has been criticized for minimizing the role of the family, school and culture in moral development. He also neglects the influence of personal motives and emotions such as pride, guilt, and shame which also affect the way people think and behave.

Cultural bias

Other critics argue that Kohlberg’s theory was developed on the basis of Western values and as such, cannot be applied to non-Western and tribal cultures that take a different approach to morality.

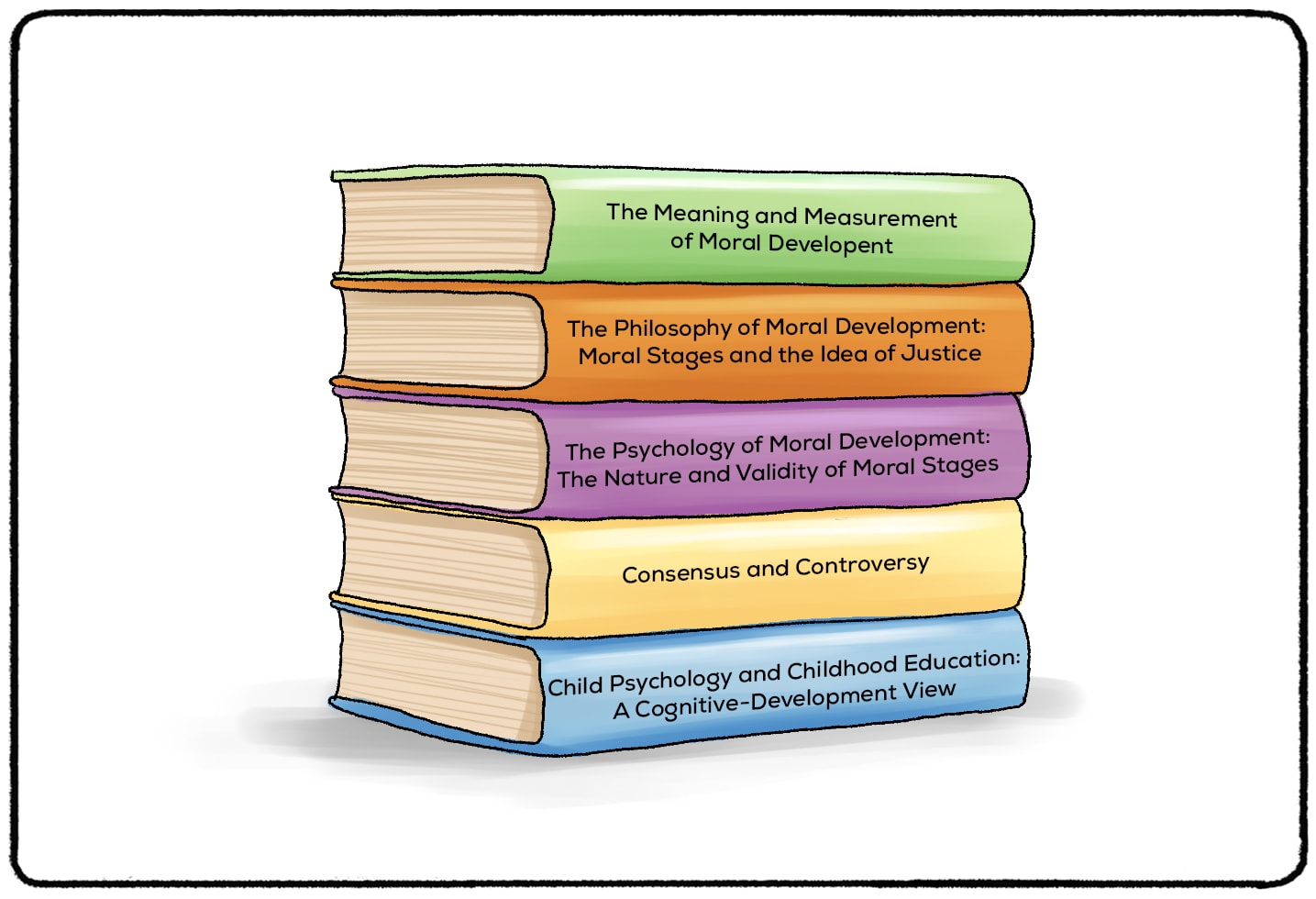

Kohlberg authored a number of groundbreaking books during his career. Some of his most well-known works include:

Kohlberg also received honorary degrees from Marquette University in Milwaukee and Loyola University in Chicago.

Kohlberg married Lucille Stigberg in 1955. They had two sons, David and Steven. While conducting research in Belize in 1971, Kohlberg contracted a severe and painful form of giardiasis. This parasitic infection as well as the demanding nature of his work eventually drained his physical health. Lawrence and Lucille Kohlberg separated in 1974 before completing their divorce in 1985.

In addition to his declining physical health, Kohlberg also experienced bouts of depression. He died on January 19, 1987 in what appeared to be an act of suicide. Kohlberg parked his car on a street close to the Boston Logan International Airport, left his identification on the front seat of his vehicle, and apparently walked into the icy waters of the Boston Harbor. His body was found some time after winter.

American Psychological Association. (2002). Eminent psychologists of the 20th century.Monitor on Psychology, 33(7). Retrieved fromhttps://www.apa.org/monitor/julaug02/eminent

Benes, K. M. (2004). Moral reasoning in children and adolescents. In T. S. Watson & C. H. Skinner (Eds.),Encyclopedia of School Psychology(pp. 192-195). New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers.

Berk, L. E. (2004).Development through the lifespan(3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Buttell, F. P. (2002). Exploring levels of moral development among sex offenders participating in community-based treatment [Abstract].Journal of Offender Rehabilitation, 34(4), 85-95.

Doorey, M. (n.d.). Lawrence Kohlberg. InEncyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved fromhttps://www.britannica.com/biography/Lawrence-Kohlberg

Gonzalez-DeHass, A. R., & Willems, P. P. (2013).Theories in educational psychology: Concise guide to meaning and practice. United Kingdom: Rowman and Littlefield Education.

Higgins-D’Alessandro, A. (2003). Kohlberg, Lawrence. In J. R. Miller, R. M. Lerner, L.B. Schiamberg, & P. M. Anderson (Eds.),Encyclopedia of Human Ecology(Vol.1, pp. 444-448). Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO.

Kroger, J. (2004). Identity in adolescence: The balance between self and other(3rd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Mangal, S. K., & Mangal, S. (2019).Psychology of learning and development. India: Phi Learning Private Limited.

Rader, A., & Rader, R. (1991). Moral development over the life cycle: Another view of stage theory. In R. R. Greene (Ed.),Human behavior theory and social work practice(2nd ed.). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Shaffer, D. R., & Kipp, K. (2014).Developmental psychology: Childhood and adolescence(9th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth.

Snarey, J. (2012).Lawrence Kohlberg: Moral biography, moral psychology, and moral pedagogy. Retrieved fromhttps://www.researchgate.net/publication/259982080_Lawrence_Kohlberg_Moral_biography_moral_psychology_and_moral_pedagogy

Related posts:Kohlberg’s Stages of Moral Development (6 Stages + Examples)Piaget’s Theory of Moral Development (4 Stages + Examples)40+ Famous Psychologists (Images + Biographies)Inductive Reasoning (Definition + Examples)Erikson’s Stages of Psychosocial Development

Related posts:

Reference this article:Practical Psychology. (2020, April).Lawrence Kohlberg (Psychologist Biography).Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/lawrence-kohlberg/.Practical Psychology. (2020, April). Lawrence Kohlberg (Psychologist Biography). Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/lawrence-kohlberg/.Copy

Reference this article:

Practical Psychology. (2020, April).Lawrence Kohlberg (Psychologist Biography).Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/lawrence-kohlberg/.Practical Psychology. (2020, April). Lawrence Kohlberg (Psychologist Biography). Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/lawrence-kohlberg/.Copy

Copy