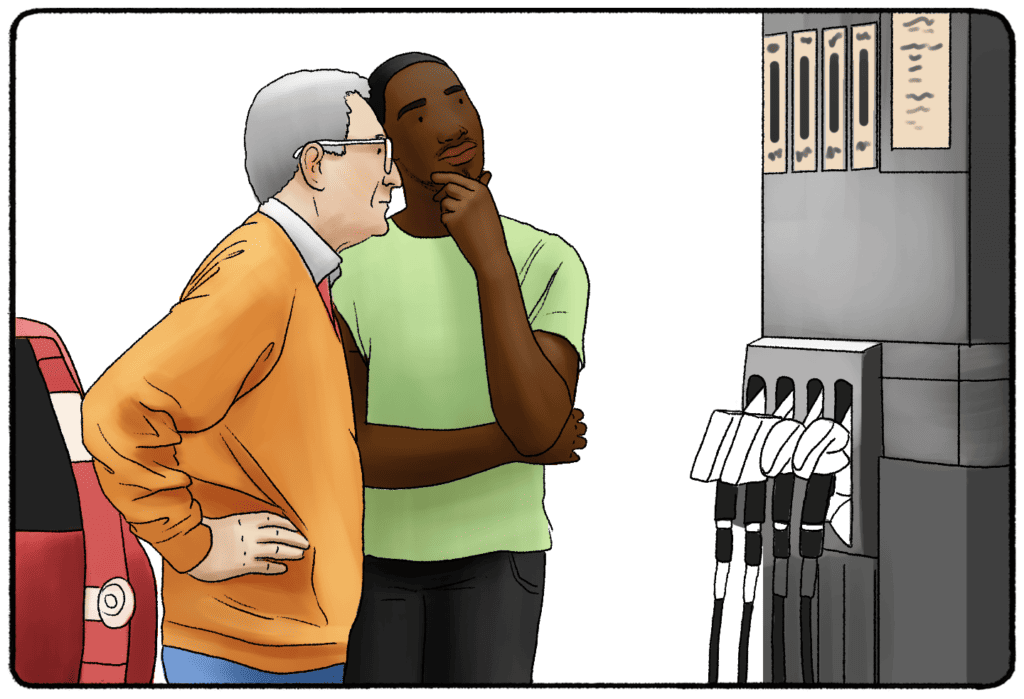

Have you ever been to a restaurant or a store with your parents and grandparents and heard them reminisce about the past? Perhaps they’ve said something like, “Back in my day, gas was only 50 cents a gallon!” While the sentiment is a mix of nostalgia and surprise at how prices have risen, there’s a deeper psychological process at play here.

They perceive current gas prices as expensive because their reference point—the anchor—is that old price of 50 cents. On the other hand, if you grew up when gas was much pricier, you might view today’s prices differently. This variance in perception, based on an initial reference point or “anchor,” is more than just a generational observation. It is a manifestation of a psychological phenomenon that can significantly influence our decisions. Welcome to the world of the anchoring effect.

The anchoring effect explains that we tend to cling to one set of beliefs or information. Often, this information is the first piece that we learn. That information influences how we perceive any supplemental information, even if it’s received years later.

anchoring bias

anchoring bias

Example of the Anchoring BiasWho Came Up With the Term “Anchoring Bias?“Combatting the Anchoring Effect in Everyday Decisions

Example of the Anchoring Bias

Who Came Up With the Term “Anchoring Bias?”

Combatting the Anchoring Effect in Everyday Decisions

When your grandparents were younger, they learned that gas was valued at 50 cents a gallon. Therefore, $2.20 for a gallon of gas is expensive. When you were younger, gas prices might have been as high as $5. To you, $2.20 for a gallon of gas isn’t expensive - in fact, it’s a pretty good deal.

You and your grandparents are both looking at a gallon of gas at $2.20. But you feel very different about that price based on the information that your beliefs areanchored to.

This is a huge phenomenon in the world of sales and economics. Anchoring determines what people are willing to pay for products. After all, if they first see paper towels sold for $5 in a store, but then look over to another brand that is selling the same product for $3, they are more likely to think that price is cheap. But if the same person first sees paper towels on sale for $1, that $3 price tag looks excessive.

Studies on the anchoring effect don’t just look at prices (although many of them do.) One of the most fascinating studies on the anchoring effect took place in the 1970s. Tversky andKahnemanwere two psychologists who looked extensively at biases. (In fact, they were some of the first researchers to look athindsight bias, which is the tendency for people to believe, after an event has occurred, that they would have predicted or expected the outcome.)

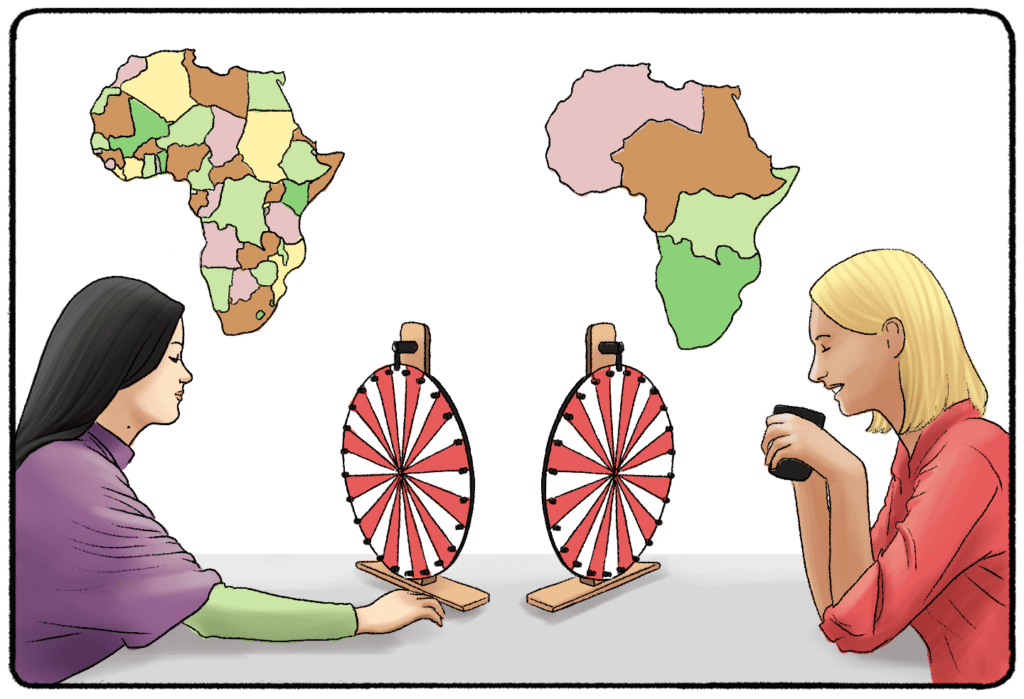

Tversky and Kahneman’s study started with a wheel with numbers from 1 to 100. The researchers spun the wheel and it landed on a number. (Let’s say it was 60.) They then asked participants to think about how many countries in the U.N. were African countries and then asked whether that number was higher or lower than the number. Finally, the researchers asked the participants to make a prediction of how many countries in the U.N. were African countries.

The wheel has no relation whatsoever to the actual number of African countries in the U.N. Yet, participants were anchored to a number that hovered around the one they were anchored to.

Why Does Anchoring Bias Occur?

Why are we anchored to one piece of information? Psychologists don’t have one for sure answer, but we can look to other phenomena that might explain why we tend to be anchored to the first piece of information that we learn.

One of these phenomena is thePrimacy Effect. The Primacy Effect is based on the idea that we are more likely to remember items that are presented at the beginning of a list rather than those presented at the middle or the end. Psychologists still have questions regardingwhywe are more likely to remember items at the beginning of a list, but likely it is due to the fact that we have a limited memory capacity or are more alert when we start to take in new information.

So information learned first is information that is more likely to stick. Once that information is in our brains, it might be hard to adjust our perspective.

These are just speculations, but it goes to show how the brain’s biases and psychological phenomena work together to form how we make decisions and see the world. I have videos on my channel about both the Primacy EffectandCognitive Dissonance.

More Examples of Anchoring Bias

Salaries are not the only thing we negotiate. As a teenager, we negotiate how late we can stay out at night. As a child, we negotiate how many vegetables we can eat before we are excused from the dinner table. The list goes on and on.

Anchoring doesn’t just impact numbers, either. Doctors may be anchored to one set of a patient’s symptoms and fail to make the proper diagnosis. Your roommate doing more work around the house may be considered more admirable if your first roommate wasn’t big on cleaning.

It’s important to understand the anchoring effect and how it impacts the way we make decisions. We can fail to see things objectively if we are stuck to one number or one point of view. When you are making decisions, ask yourself, “What information am I comparing my decision to? Am I looking at this objectively, or am I ‘anchored’ to one choice?”

While the anchoring effect is a deeply ingrained cognitive bias, there are strategies that can help you become more aware of its influence and make more objective decisions. Here are some steps you can take:

By actively integrating these strategies into your decision-making processes, you can mitigate the effects of anchoring bias and make choices that are more in line with your true preferences and values.

Related posts:The Psychology of Long Distance RelationshipsOperant Conditioning (Examples + Research)Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI Test)Experimenter Bias (Definition + Examples)Variable Interval Reinforcement Schedule (Examples)

Related posts:

Reference this article:Practical Psychology. (2019, October).Anchoring Bias (Definition + Examples).Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/anchoring-bias-definition-examples/.Practical Psychology. (2019, October). Anchoring Bias (Definition + Examples). Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/anchoring-bias-definition-examples/.Copy

Reference this article:

Practical Psychology. (2019, October).Anchoring Bias (Definition + Examples).Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/anchoring-bias-definition-examples/.Practical Psychology. (2019, October). Anchoring Bias (Definition + Examples). Retrieved from https://practicalpie.com/anchoring-bias-definition-examples/.Copy

Copy